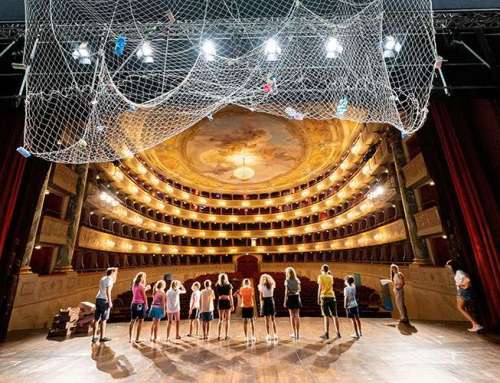

The Miser is the next title on the bill for the Prose Season of the Donizetti Theatre Foundation, scheduled in the main city theatre from Saturday, February 8 to Sunday, February 16: Molière’s famous comedy will feature Ugo Dighero as Harpagon, an actor known for comic roles, already highly appreciated protagonist of works by Stefano Benni and Dario Fo, who is facing a great classic for the first time. Alongside him will be: Mariangeles Torres, Fabio Barone, Stefano Dilauro, Cristian Giammarini, Paolo Li Volsi, Elisabetta Mazzullo, Rebecca Redaelli and Luigi Saravo. The latter is also directing the play.

On Thursday, February 13 at the “M. Tremaglia” Music Hall of the Donizetti Theatre (6 pm) there will be a meeting about the show with Ugo Dighero and the company. Maria Grazia Panigada, Artistic Director of the Prose Season and Other Paths, will coordinate. Free entry with reservation by registering at the Eventbrite link published on the Donizetti Theatre website.

In Molière’s comedy, we witness an epic clash between feelings and money. The protagonist is willing to sacrifice his children’s happiness, just to avoid having to provide them with a dowry and instead acquire new wealth through their marriages. Saravo’s direction sets the show in a dimension that refers to our daily life, juggling different temporal references, from smartphones to 1970s clothes to commercials that torment Harpagon (advertising is the devil that could tempt him to spend his beloved money). Even Paolo Silvestri’s original music moves on different planes, while Letizia Russo’s new translation, fresh and direct, helps give the whole a contemporary rhythm. “The narrative of Molière’s The Miser revolves around a central theme, to which all others reconnect: money,” writes Luigi Saravo in his director’s notes, “Money and its conservation, its squandering, gambling, the purchase of goods and their degradation leading to the purchase of new goods, loans, interests and the power relationships that derive from money. In our consumption-oriented contemporary world, defined by the need to circulate money in pursuit of infinite economic growth, Harpagon’s conservative and immobilist gesture, from a financial point of view, sounds subversive to us, in stark opposition to consumerist tyranny, to advertising which is its engine, and to that pathology of desire that sees substitution as its foundation. If we analyze the core of the text, namely the conflict between Harpagon and his entourage, we are faced with the conflict of two economic visions: a consumerist one of twentieth-century capitalist stamp and a relatively new, conservative one, which opposes consumption and is oriented towards the conservation of goods, their reuse, their exchange and, finally, their protection, first and foremost those goods defined as ‘natural goods’. We don’t mean to say that Harpagon is a positive hero, that he is moved by an ideological drive, but certainly that with his attitude he clearly stands in opposition to twentieth-century capitalist economics and more in line with the conservative vision.” “Around him move the other characters, apparently victims of his tyranny, but, in reality, figures devoted to ideals well recognizable in this context shift. These figures lament their imprisonment, their forced submission to Harpagon’s will, but in reality they are subjected above all to the economic bond that ties them to him, potentially capable of escaping that tyranny by leaving the house and the assets promised by inheritances and salaries. And finally, to put it with Voltaire: men hate those they call misers only because they can get nothing out of them,” concludes Luigi Saravo.