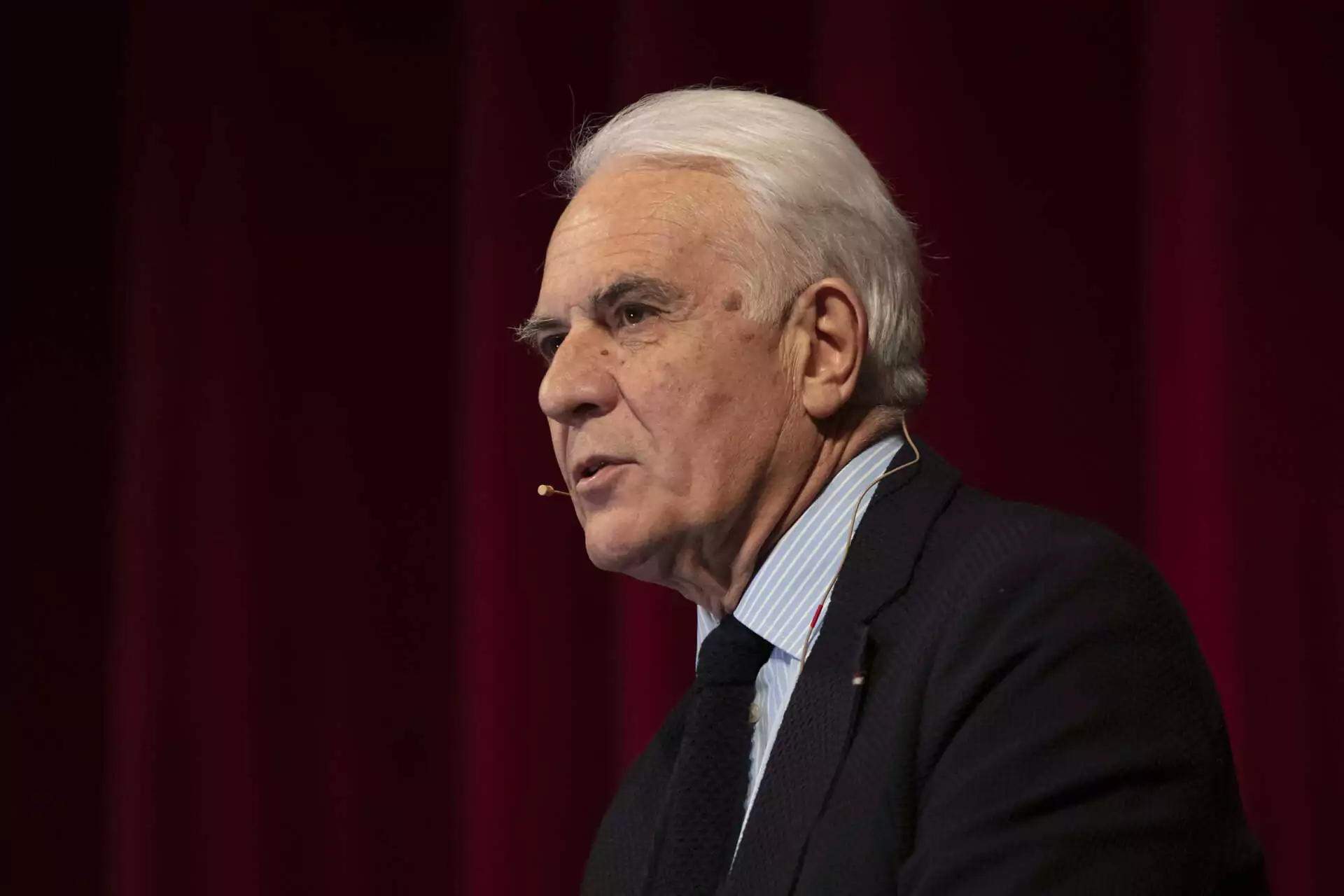

Luigi Mascilli Migliorini | Robespierre: at the heart of the Revolution.

Teatro DonizettiThe well-behaved lawyer of a provincial town is a symbol of the French Revolution, its illusions, its horrors. We do not know when the uneasiness of a bourgeois soul manifested itself in an "incorruptibility" later embodied in the sacred principles of a Revolution, despite itself, inevitably destined to corrupt itself. A member of the Accademia dei Lincei, former president of SISEM and professor of modern history at L'Orientale University, Luigi Mascilli Migliorini is one of the leading scholars of the Napoleonic age and the Restoration in Europe, to whom he has dedicated two important biographies, Napoleon, Salerno Editrice (2002 and new edition 2015) and Metternich, Salerno Editrice (2014). He is Commandeur de l'Ordre des Palmes Académiques, Chevalier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres of the French Republic and invited professor at the École Normale Supérieure in Paris and the Catholic University of Santiago de Chile. He is on the scientific committee of Napoleon's Correspondance at the publisher Fayard. For Laterza he has published, among others, The Modern Age. A global history (2022). At the end of the meeting, the author will be available to the audience for signacopies.

Miser.

Teatro DonizettiThursday, February 13, 2025, 6:00 PM | Music Hall - Teatro Donizetti Around L'AVARO Meeting with Ugo Dighero and the company Maria Grazia Panigada coordinates the meeting. Ugo Dighero, already a highly appreciated protagonist of works by Stefano Benni and Dario Fo, confronts a great classic for the first time, playing Harpagone in the new production directed by Luigi Saravo. In Molière 's comedy we witness an epic clash between feelings and money. The protagonist is willing to sacrifice his children's happiness so that he does not have to provide them with a dowry and rather acquire new wealth through their marriages. Saravo's direction sets the play in a dimension that harks back to our daily lives, juggling different temporal references, from smartphones to 1970s clothes to the commercials that torment Arpagone (advertising is the devil that could lead him into the temptation of spending his beloved money). Paolo Silvestri's original music also moves on different planes, while Letizia Russo's fresh and direct new translation helps give the whole thing a contemporary rhythm. The narration of The Miser by Molière revolves around a central theme, to which all the others reconnect: money. Money and its preservation, its squandering, gambling, the purchase of goods and their degradation leading to the purchase of new goods, loans, interest and the power relations that descend from money. In our consumer-oriented contemporary world, defined by the need to circulate money in pursuit of infinite economic growth, Harpagon's conservative and immovable gesture, from a financial point of view, sounds to us as subversive, in stark opposition to consumerist tyranny, the advertising that drives it, and that pathology of desire that sees substitution as its foundation. If we analyze the core of the text, that is, the conflict between Harpagon and his entourage, we are confronted with the conflict of two economic visions: a consumerist one of the twentieth-century capitalist type and a, relatively new, conservative one, which opposes consumption and is oriented toward the preservation of goods, their reuse, their exchange and, finally, the protection of them, first among all those goods defined as "natural goods." We do not want to say that Harpagon is a positive hero, that he is moved by an ideological impulse, but, certainly, that with his attitude he stands clearly in opposition to the twentieth-century capitalist economy and more in line with the conservative vision. Around him move the other characters, apparently victims of his tyranny, but, in reality, figures devoted to ideals clearly recognizable in this shift of context. These figures lament their imprisonment, their forced submission to Harpagon's will, but in reality they are submissive above all to the economic bond that binds them to him, potentially able to escape that tyranny by abandoning their homes and the possessions promised by inheritance and wages. And finally, as Voltaire puts it: men hate those they call misers only because they can get nothing out of them. Louis Saravo