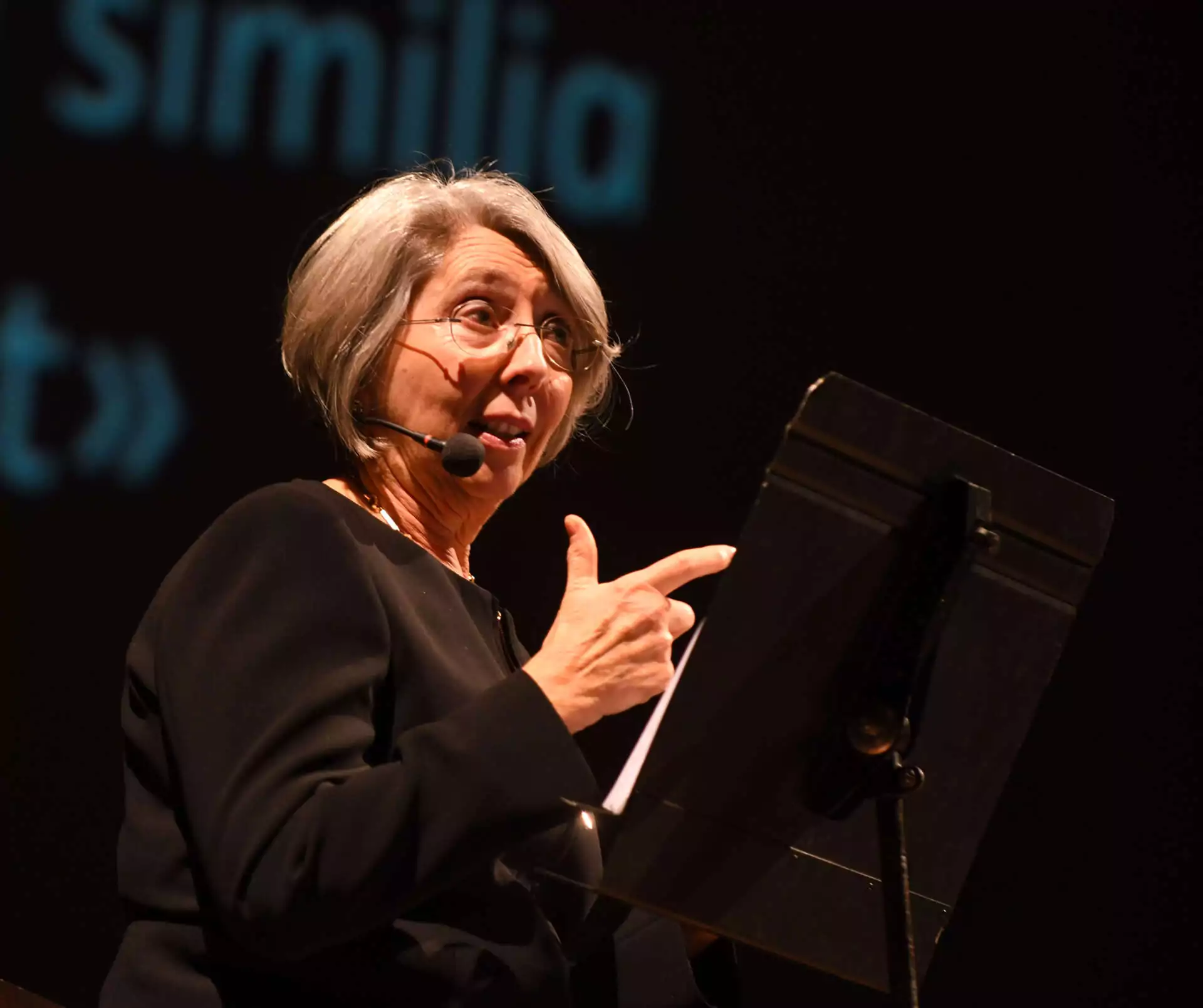

Maria Giuseppina Muzzarelli | Joan of Arc: a woman in arms

Teatro DonizettiShe is a girl, but fights like a man; she is a Christian virgin, but wears men's clothes; she feels a direct relationship with God, but does not recognize the mediation of the Church. Revered as a saint, she has become a myth, and not only for the French. Many questions remain, however, about this young woman in arms who was burned at the stake at age 19. Maria Giuseppina Muzzarelli has taught Medieval History, History of Cities and History and Cultural Heritage of Fashion at the University of Bologna. She works on the history of mentality and society. Among her publications: Fishers of men. Preachers and squares at the end of the Middle Ages. (2005); An Italian at the Court of France. Christine de Pizan intellectual and woman (new edition 2017); Covered head. Stories of women and veils (new 2018 edition); The rules of luxury. Appearances and everyday life from the Middle Ages to the modern age. (2020). Per Laterza è autrice di In the hands of women. Feeding, healing, poisoning from the Middle Ages to the present. (2013), Mothers, missed mothers, almost mothers. Six medieval stories (2021) e La señora. Life and Adventures of Gracia Nasi (2024). At the end of the meeting, the author will be available to the audience for signacopies.

Miser.

Teatro DonizettiThursday, February 13, 2025, 6:00 PM | Music Hall - Teatro Donizetti Around L'AVARO Meeting with Ugo Dighero and the company Maria Grazia Panigada coordinates the meeting. Ugo Dighero, already a highly appreciated protagonist of works by Stefano Benni and Dario Fo, confronts a great classic for the first time, playing Harpagone in the new production directed by Luigi Saravo. In Molière 's comedy we witness an epic clash between feelings and money. The protagonist is willing to sacrifice his children's happiness so that he does not have to provide them with a dowry and rather acquire new wealth through their marriages. Saravo's direction sets the play in a dimension that harks back to our daily lives, juggling different temporal references, from smartphones to 1970s clothes to the commercials that torment Arpagone (advertising is the devil that could lead him into the temptation of spending his beloved money). Paolo Silvestri's original music also moves on different planes, while Letizia Russo's fresh and direct new translation helps give the whole thing a contemporary rhythm. The narration of The Miser by Molière revolves around a central theme, to which all the others reconnect: money. Money and its preservation, its squandering, gambling, the purchase of goods and their degradation leading to the purchase of new goods, loans, interest and the power relations that descend from money. In our consumer-oriented contemporary world, defined by the need to circulate money in pursuit of infinite economic growth, Harpagon's conservative and immovable gesture, from a financial point of view, sounds to us as subversive, in stark opposition to consumerist tyranny, the advertising that drives it, and that pathology of desire that sees substitution as its foundation. If we analyze the core of the text, that is, the conflict between Harpagon and his entourage, we are confronted with the conflict of two economic visions: a consumerist one of the twentieth-century capitalist type and a, relatively new, conservative one, which opposes consumption and is oriented toward the preservation of goods, their reuse, their exchange and, finally, the protection of them, first among all those goods defined as "natural goods." We do not want to say that Harpagon is a positive hero, that he is moved by an ideological impulse, but, certainly, that with his attitude he stands clearly in opposition to the twentieth-century capitalist economy and more in line with the conservative vision. Around him move the other characters, apparently victims of his tyranny, but, in reality, figures devoted to ideals clearly recognizable in this shift of context. These figures lament their imprisonment, their forced submission to Harpagon's will, but in reality they are submissive above all to the economic bond that binds them to him, potentially able to escape that tyranny by abandoning their homes and the possessions promised by inheritance and wages. And finally, as Voltaire puts it: men hate those they call misers only because they can get nothing out of them. Louis Saravo